CITYSPACE: SAVING MURAD KHANE

Afghanistan's other casualties: an unusual young Scot is involved in a heroic effort to preserve the heritage of battered historic Kabul writes LISA ROCHON

LISA ROCHON Saturday, May 26 2007

As with any disaster, natural or manmade, there are two kinds of destruction going on in Afghanistan: that caused by the war and the wrecking by city planners of what remains. The looming urban disaster that concerns me is likely not on the radar screens of Prime Minister Stephen Harper or the good Canadian troops stationed in the south of Afghanistan. But it should be. What's at risk is the survival of historic Kabul, a neighbourhood of elaborately decorated mud buildings - tea houses, historic mosques, public baths - that city planners would like to eliminate so as to allow a six-lane highway to run through it.

It's only fitting that the crusade to save old Kabul (photo) is being led by Rory Stewart, the iconoclastic Scottish adventurer and author of The Places in Between. He was asked to become involved by Prince Charles, whose friendship with Afghan President Hamid Karzai led to the Prince setting up the Turquoise Mountain Foundation, aimed at both historical restoration and teaching youth traditional skills. Now, the organization is countering the city's threats to pull down the historic neighbourhood of Murad Khane with an initiative to restore the adobe structures in a tight warren of streets north of the Kabul River.

More than 100 people from the neighbourhood, including some women and orphans, are being employed by the foundation to restore 200-year old buildings. More than restoration, though, we're talking about the protection of collective memory and the rising up of civic pride. Houses are being rebuilt, mud walls are being reinforced and piles of garbage, sometimes several metres high, are being cleared for the first time from the streets. In a district where 615 residents function without toilets or sewage provisions, running water is finally being supplied to the area.

Stewart walked across Afghanistan in the winter of 2002, just weeks after the Taliban had been driven out by coalition forces. His critically acclaimed book The Places in Between is a stunning account of his harrowing journey. He writes of once-refined cities stripped down to shantytowns, Hazara villages burned to become emaciated versions of their original selves and people's circumstances terribly reduced first by the Russians, then the Taliban and bloody skirmishes between neighbours sometimes living only a few kilometres apart.

Stewart's is a life well-lived. In the early 1990s, he was an Eton-educated summer tutor of Prince William and Prince Harry, a job that led to the friendship and respect of the Prince of Wales. Just into his 30s, he was awarded the Order of the British Empire in 2004 for a decade of foreign service that included, during the previous year, serving as deputy governor of two southern provinces in Iraq.

When he walked across Afghanistan, he was called a "nutter" by some fellow Brits stationed in a remote outpost, a bit of homespun humour that cheered Stewart to continue to trudge through a winter blizzard that day. He walked an average of 40 kilometres a day.

Sufficiently intrigued, I decided to call Kabul during the holiday weekend from my cedar cottage in Ontario. It was early in the morning, the fire wasn't throwing much heat and my hands were freezing. When Stewart picked up, I was looking through the green veil of Jack pines to the lake and the four islands you want to swim to when the water is warmer.

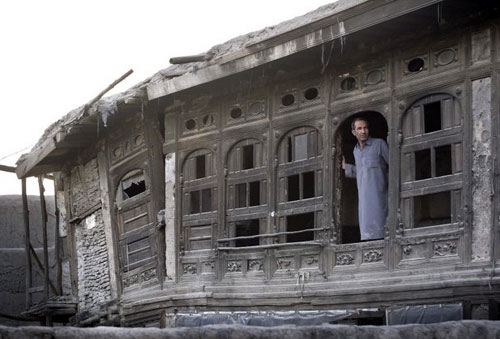

Stewart's neck, on the other hand, was being burned by the hot Afghanistan sun. Indeed, we were worlds apart. "I'm standing in the middle of a 19th-century fort," says Stewart, who sounds more like an art historian turned urban designer than the British foreign officer he once was. "It's made up of mud walls with bleached cedar windows carved with Buddhist motifs, Islamic geometric designs, art deco."

Is Old Kabul coming down? "It's difficult to judge," says Stewart. "The master plan of the old city is being written and rewritten continually," but "because of the work we've done in the last 14 months, I think we've made a lot of progress." In this case, progress depends on the pressure exerted by Stewart, his foundation and the rest of the international community. The idea, simply put, is to make it impossible for the city planners to tear something that has started to sparkle again.

The Turquoise Mountain Foundation is named for the 12th-century capital of the Silk Road empire, a place marked only by a towering minaret, which Stewart happened upon during his journey. Tragically, given lack of leadership by the international community, the site has been looted and pillaged by the locals keen to sell their findings for a pittance. "The Turquoise Mountain was only the most dramatic and most recent victim of a general destruction of Afghanistan's cultural heritage," wrote Stewart in his book. "A month after I left the village, items from [the valley of] Jam [site of the Turquoise Mountain] - described as Seljuk or Persian to conceal their Afghan origin - were being offered on the London art market."In Kabul, the gorgeous, idiosyncratic detailing of the abode structures, the result of layering of culture and religion, is increasingly under threat. For one thing, the nation's capital has exploded from a population of one million in 2001 to 4.5 million today - the result of floods of Afghan refugees returning from Pakistan and Iran. Besides, distinctive architecture mattered not at all to the Soviet and East German planners who dictated in a 1978 plan the future of Kabul in which anonymous concrete and brick block towers would replace the fine vernacular stock of buildings.

The civil war of 1989-1992 interrupted their short-sighted plans - neglect is often the saving of historic neighbourhoods around the world - but since a relative peace has descended on Kabul, the planners have dusted off the brutish Soviet-style plan.

However, "To some extent, they're coming around," says Stewart, on the phone from Kabul. "If we'd started with a lot of bureaucratic talk and documents, we might have been met with utter skepticism. But we've set up a school, cleaned the garbage. The real thing I want to get is a full legal guarantee for the preservation of the entire area."

Initially, Prince Charles imagined the establishment of a centre in which locals could be taught traditional crafts, such as metalworking or woodcarving. Many of the local artisans had fled the area or, indeed, the country.

During his six-week journey across the country, Stewart had observed the slipping away of culture in Afghanistan, how, as he wrote in his book, "religion, language, and social practices were becoming homogenized, and how little interest people took in ancient history." He wanted to participate in the Prince's plan, but insisted that the newly trained artists be part of an urgent cause: revitalizing and potentially saving the historic neighbourhood of Murad Khane.

Murad Khane is a place of crowded marketplaces, with some 300 handcarts selling everything from Chinese alarm clocks to sandals made from rubber tires. Stewart walks the streets to meet daily with the street bosses, collecting petitions supporting the foundation's work, marked by the illiterate with thumbprints. Drainage ditches are being dug and solar panels installed on some of the roofs. "What we're looking at here is a robust, functioning neighbourhood. We're not interested in a Disneyfied place that is frozen in time."

Since the Turquoise Mountain Foundation was established last year, it has attracted some impressive recruits, including Jemima Montagu, a former curator at the Tate Modern who now serves as its director of culture and education. Rebecca Tunstall, a lecturer in housing at the London School of Economics, has consulted with the team on urban regeneration and development, and there have been architects and building conservationists pitching in from Zurich and London. The small team lives together in a ramshackle mud building and shares dinner in the evening.

The Prince of Wales and the Prince's Trust have provided key financial support for the foundation, and important backing has come from the Aga Khan Development Network. But money is tight. Stewart spends much of his time fundraising in the Middle East, particularly the Persian Gulf states. More money is urgently needed, he says, as the foundation only has about six months of operational funds in the bank.

Afghanistan is a country that has known a continuity of violence and destruction, but also healing. When Stewart walked across Afghanistan, he effectively retraced the footsteps of Babur, the first emperor of Mughal India, who wrote in his journals of the desperation and beauty of his journey.

After reaching the western edge of Kabul, Babur noted that there were 33 different sorts of tulips growing with wild abandon in the mountains, some with the perfume of roses. In 1519, Babur planted two plane trees on a hill on what would become the site of the emperor's tomb and a lush garden in Kabul.

Stewart has since identified the stumps of what were once glorious trees, the result of another vicious act by the Taliban. The Aga Khan Trust for Culture has been working over the last few years to revitalize the historic Bagh-e-Babur garden as a major public open space.

Human beings can be cruel and illogical, but they are also capable of believing in something better for the future. Old Kabul should be allowed to stand. The plane trees will surely be replanted. And cut down, no doubt, during another sorry time.